For My Father

For those who were around my family and might remember back to the year 1987, my dad died suddenly the night before my Bar Mitzvah, two days after I turned thirteen. My teenage years were pretty rocky and dramatic, and there were few people I stayed in touch with who knew him. I desperately needed community that understood me and I did not find it in the world of my parents.

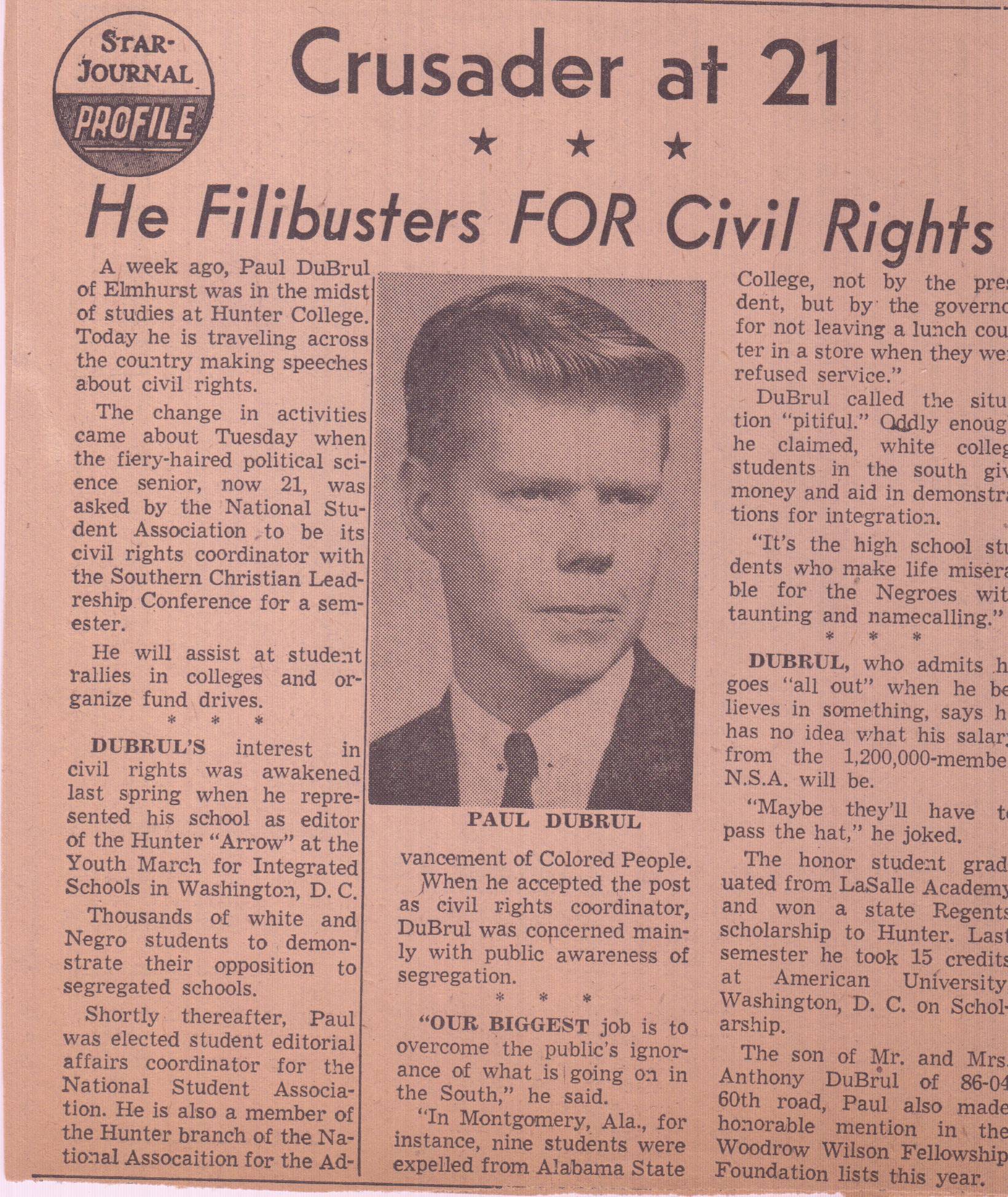

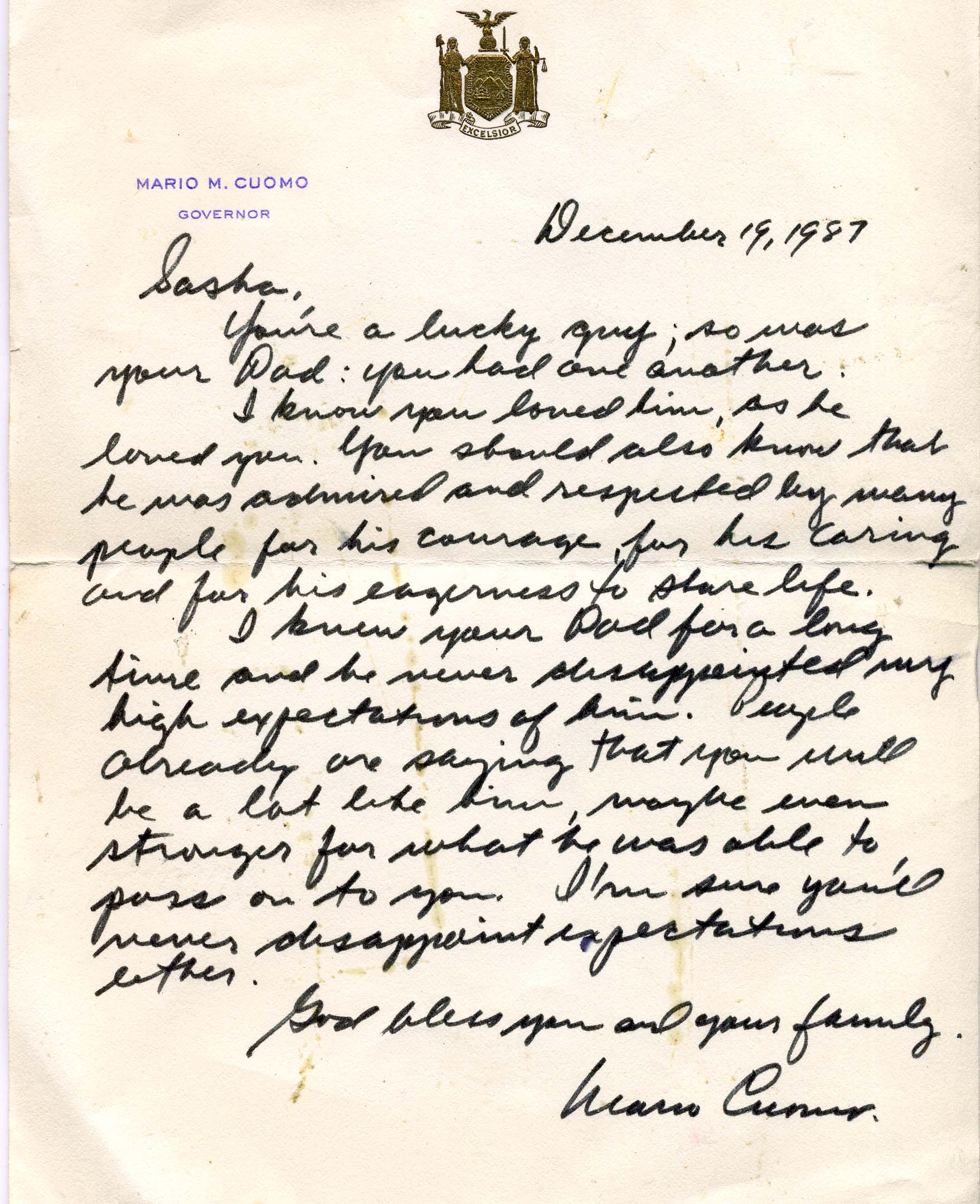

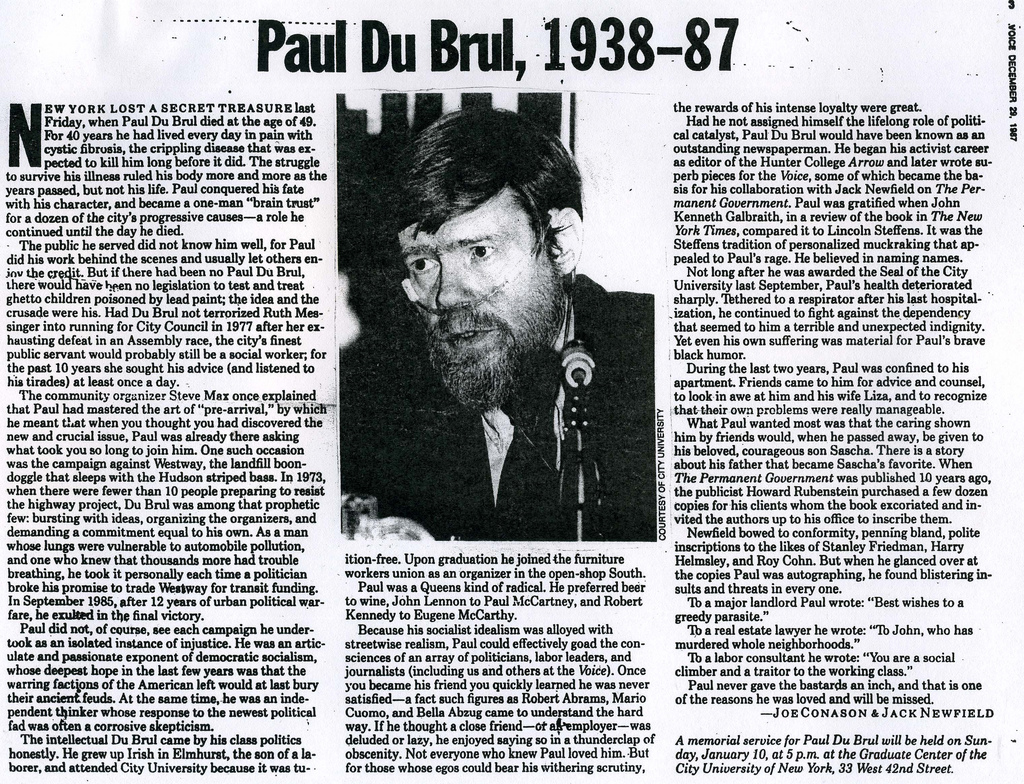

My father was from a dying era of journalists: he wrote with a manual typewriter and never came close to seeing the rise of the Internet age. He was a committed Socialist who died before the Berlin Wall fell and the whole geopolitical structure of the world was reformulated. Although he was politically radical, he was actually culturally very straight, and chose to work within the system to make change. My dad ended up being a speechwriter for many people, including Governor Mario Cuomo. I was just watching an old video of the community organizer Steve Max giving a talk about my dad and he said: “Speechwriting for Paul meant inserting clarity and anti-corporate populism into the remarks of people who often wouldn’t normally be known for their clarity and anti-corporate populism.” I believe this summed up a lot of his work.

Paul DuBrul had very strong opinions about the world and clearly wanted me, his only child, to do important things with my life. It has always been a lot of internal pressure that I’ve carried around, and anyone who knows me well has seen how that pressure has played itself out in my personal life and movement work. I think it’s only natural that I’ve spent years comparing myself to him and wondering what he would have thought of the choices I’ve made and the unconventional life I’ve chosen to lead.

I definitely inherited my father’s rage against social injustice. I inherited his love of reading and writing and studying history. I inherited his passion for naming names and confronting institutional power directly. I inherited his ability to think on systemic levels and envision large-scale transformational change. I inherited his sense that there was never enough time.

I did not inherit his interest in electoral politics. I did not inherit his conservative 1950’s era ideas about gender relations and sexuality. I did not inherit his New York City centrism or his fear of foreign travel. I thankfully did not inherit his lack of breath or crippling illness.

My dad and I came from such different worlds and generations. He was raised working class Irish-Catholic in Elmhurst, Queens. I was raised a middle class white kid on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, with very little sense of the immigrant cultural roots or the hardship of my forbearers. He was indoctrinated and rebelled from the Catholic Church after being beaten by nuns as a child. I was indoctrinated and rebelled from MTV and 1980’s pop culture after spending much of my childhood in front of the television screen.

The year after my dad died I was appointed to David Dinkins’ “Youth Advisory Committee” that met weekly at City Hall to discuss local political issues and supposedly “consult” with the mayor. It was a group for aspiring young politicians, a great thing to put on a college résumé, and it seemed like such irrelevant bullshit to my 14 year old life. I dropped out half way through and joined a group of young anarchists called the New York Direct Action Correspondence who met in a dark basement around the corner from Tompkins Square Park. I came of age amidst the squatter community on the Lower East Side and never went back to the straight world of Upper West Side progressive politics.

For those of his friends who’ve been out of touch with me since I was a child, I’ve had a really interesting life (you can read a few things about it here.) I spent quite a bit of time in psychiatric hospitals over the years, beginning when I was 18, and in my late 20’s I helped to create a community many thousands deep, called the Icarus Project. It’s an organization for people, like me, who’s been in the psychiatric system and want to change the whole paradigm of what gets considered “mental health” and “mental illness.”

I clearly got the fire and passion to do this work from both of my parents, but it has been my father in particular who has served as a role model to me as someone who struggled with serious health issues and managed to rewrite the script of his illness.

As I’ve gotten older I’ve come to put my father’s Socialist politics in perspective and see that he was part of one shard of a fragmented Left. I don’t know what he would think of my countercultural affiliations or my radical feminism or my general lack of interest in conventional social norms, but I’m sure he would be impressed at how much passion and drive I’ve put into my life’s work. I like to think that his friends would be interested as well.